|

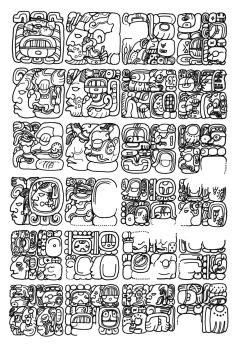

| From the Linda Schele Drawing Collection |

Most of my personal study focuses on the ancient Mediterranean world, so ancient Mesoamerican civilizations and their languages are about half a world outside of my academic comfort zone. But in anticipation of my upcoming visit to the Ancient Maya exhibit at the Science Museum of Minnesota, I thought I'd add at least a rudimentary post on ancient Maya "hieroglyphics" to our ancient language resource page. If you are interested in Mesoamerican civilizations you might want to check out some of these resources, and maybe try your hand at learning some of the Maya "hieroglyphs" (it is a logosyllabic script, popularly called hieroglyphic because it reminds us of Egyptian). If, like me, your ancient gaze lies elsewhere, it is still a fruitful exercise to learn something about the language. For one thing, its hundreds of symbols will make any challenges you encounter with ancient alphabet or even abugida scripts seem less daunting. But there is also value in the comparative study of ancient languages, writing systems, and cultures. What comparative light might the Mayans shed on your own areas of research?

It's worth noting that the Mayan language family is alive -- millions still speak the Mayan languages today, and there have been some attempts to reclaim the ancient writing system:

Although people tend to think of the Maya as a lost civilization, there are still more than 10 million people living in Mexico and Guatemala who are ethnically Maya. While some are scholars, teachers, lawyers or modern professionals of all sorts, many live in ways little different from how their ancestors lived, in thatch-roofed structures with walls of wood poles and mud. They often have corn, the sacred grain and a staple in their diet, planted near the house, and practice rituals descended directly from those practiced a few thousand years ago.I won't spend any time touching on the basics of Maya hieroglyphs, because the link to Kettunen and Helmke's text below gives a great introduction. Check out the resources, and if you come across any good ones I've missed let me know.

But while they still speak Maya languages, contemporary Maya were until recently unable to read Maya writing. At the invitation of indigenous Maya academics in Guatemala, Schele and colleagues, including Nikolai Grube, organized 13 Hieroglyphic Workshops in Guatemala and Mexico between 1988 and 1997. For the first time in history, Maya could read and ultimately write using the hieroglyphic inscriptions of their ancestors. Through CHAAAC, Grube and others, including university graduate students, continue that work.

Maya hieroglyphic writing is now part of the curriculum in Maya schools. Maya newspapers and publications spell headlines and titles in Maya hieroglyphics as well as roman letters, and children have learned to write their names using the Maya writing system.

Most important, learning their writing system has given the Maya the tools to recover and reclaim their history.

“The Maya are people who have had their history and mental sovereignty ripped away from them and kept away from them for 500 years,” Schele said, “and it is a basic human right to control your own history.” (http://www.utexas.edu/features/archive/2003/mayameet.html)

Kettunen, Harri and Christophe Helmke. Introduction to Maya Hieroglyphs.

"Maya Hieroglyphic Writing" from the Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies, Inc.

Cracking the Maya Code (VIDEO)

Corpus of Maya Hieroglyphic Inscriptions Program through the Peabody Museum

The Mesoamerica Center

Mesoweb

Graduate programs in Mesoamerican Studies

No comments:

Post a Comment